Associations

This guide covers the association features of Leoric. After reading this guide, you will know:

- How to declare assocations between models.

- How to understand the various types of associations.

Table of Contents

Why Associations

With associations well defined, developers can pull structured data with a single query such as:

const shop = await Shop.findOne({ id }).with('items', 'owner')

// => Shop { id: 1,

// name: 'Barracks',

// items: [ Item { name: "Wirt's Leg" }, ... ],

// owner: User { name: 'Tyreal' } }

Types of Associations

Leoric supports four types of associations:

belongsTo()hasMany()hasMany({ through })hasOne()

Associations can be declared within the Model.describe() method. For example, by declaring a shop belongsTo() its owner, you’re telling Leoric that when Shop.find().with('owner'), Leoric should join the table of owners, load the data, and instantiate shop.owner on the found objects.

There are four equivalent decorators for projects written in TypeScript

@BelongsTo()@HasMany()@HasMany({ through })@HasOne()

The major difference between static method and decorators for associations is that the first parameter can be omitted in the decorator equivalent. For example, Post.belongsTo('user') declared with decorator is like below:

class Post {

@BelongsTo()

user: User

}

belongsTo()

A belongsTo() association sets up a one-to-one or many-to-one relationship. For example, a shop can have many items as it finds fit. On the other hand, an item can belongsTo() to exactly one shop. We can declare the Item this way:

class Item extends Bone {

static initialize() {

this.belongsTo('shop')

}

}

The TypeScript equivalent with decorator is like below:

class Item extends Bone {

@BelongsTo()

shop: Shop;

}

Leoric locates the model class Shop automatically by capitalizing shop as the model name. If that’s not the case, we can specify the model name explicitly by passing className:

class Item extends Bone {

static initialize() {

this.belongsTo('shop', { className: 'Seller' })

}

}

The TypeScript equivalent with decorator is like below:

class Item extends Bone {

@BelongsTo({ className: 'Seller' })

shop: Shop;

}

Please be noted that the value passed to

classNameis a string rather than the actual model class. Tossing the actual classes back and forth between the two parties of an association atModel.describe()phase can be error prone because it causes cyclic dependencies.

As you can tell from the ER diagram, the foreign key used to associate a belongsTo() relationship is located on the model that initiates it. The name of the foreign key is found by uncapitalizing the target model’s name and then appending an Id. In this case, the foerign key is converted from Shop to shopId.

Leoric has two sets of names maintained under the hood. One is the attribute names of the model, which usually are in camel case to be compliant with common JavaScript coding conventions. The other is the columns names of the actual table, which may be in camel case but usually are in snake case.

To override foreign key, we can specify it explicitly:

class Item extends Bone {

static initialize() {

this.belongsTo('shop', { foreignKey: 'sellerId' })

}

}

The TypeScript equivalent with decorator is like below:

class Item extends Bone {

@BelongsTo({ foreignKey: 'sellerId' })

shop: Shop;

}

hasMany()

If you look this ER diagram from the shops point of view, you may notice that there is a hasMany() association too. The shop hasMany() items:

class Shop extends Bone {

static initialize() {

this.hasMany('items')

}

}

The TypeScript equivalent with decorator is like below:

class Shop extends Bone {

@HasMany()

items: Item[];

}

Please be noted that unlike

belongsTo(), the name passed tohasMany()is usually in plural.

The way Leoric locates the actual model class is quite similar. It starts with singularizing the name, then capitalizing. In this case, items get singularized to item, and then Item is used to look for the actual model class.

To override the model name, we can specify it explicitly:

class Shop extends Bone {

static initialize() {

this.hasMany('items', { className: 'Commodity' })

}

}

The TypeScript equivalent with decorator is like below:

class Shop extends Bone {

// It might be able to deduce the className from `Commodify[]` type

@HasMany({ className: 'Commodity' })

items: Commodity[];

}

As you can tell from the ER diagram, the foreign key used to join two tables is located at the target table, items. To override the foreign key, just pass it to the option of hasMany():

class Shop extends Bone {

static initialize() {

this.hasMany('items', { foreignKey: 'sellerId' })

}

}

The TypeScript equivalent with decorator is like below:

class Shop extends Bone {

@HasMany({ foreignKey: 'sellerId' })

items: Item[];

}

hasMany({ through })

The world of entity relationships doesn’t consist of one-to-one or one-to-many associations only. There are many scenarios that require a many-to-many association to be setup. However, in relational databases many-to-many between two tables isn’t possible by nature. To accompish this, we need to introduce an intermediate table to bridge the associations.

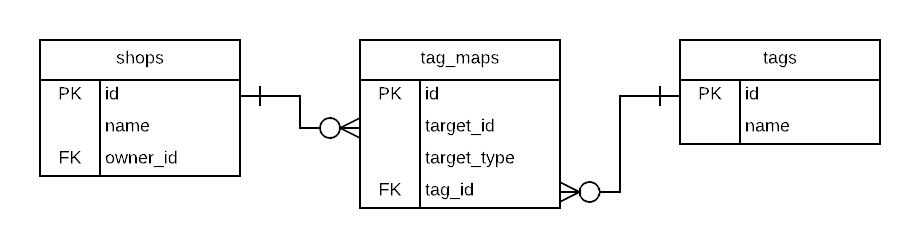

Take following tag system for example:

A shop can have as many tags as it see fit. And a tag can be related to as many shops as it like. The actual relationships are recorded in the tag_maps table. To find associations either from the shop or the tag, the query needs to go through tag_maps first.

As you may have noticed already, the

tag_mapsdoesn’t necessarily relate toshopsas their targets in this ER model. It supports generic targets with thetarget_typecolumn. In this way, thetagscan have many-to-many associations to any other models.

hasMany({ through }) is just the method that helps us setup that kind of associations. From Shop’s point of view:

class Shop extends Bone {

static initialize() {

// the extra where is needed if you fancy this generic tag system

this.hasMany('tagMaps', { foreignKey: 'targetId', where: { targetType: 0 } })

this.hasMany('tags', { through: 'tagMaps' })

}

}

The TypeScript equivalent with decorator is like below:

class Shop extends Bone {

@HasMany({ foreignKey: 'targetId', where: { targetType: 0 } })

tagMaps: TagMap[];

@HasMany({ through: 'tagMaps' })

tags: Tag[];

}

On Tag’s side:

class Tag extends Bone {

static initialize() {

this.hasMany('shopTagMaps', { className: 'TagMap', where: { targetType: 0 } })

this.hasMany('shops', { through: 'shopTagMaps' })

}

}

The TypeScript equivalent with decorator is like below:

class Shop extends Bone {

@HasMany({ className: 'TagMap', foreignKey: 'targetId', where: { targetType: 0 } })

shopTagMaps: TagMap[];

@HasMany({ through: 'shopTagMaps' })

shops: Tag[];

}

If suddenly our business requires us to apply the tag system to items too, the changes needed on Tag model is trivial:

class Tag extends Bone {

static initialize() {

this.hasMany('shopTagMaps', { className: 'TagMap', where: { targetType: 0 } })

this.hasMany('shops', { through: 'shopTagMaps' })

+ this.hasMany('itemTagMaps', { className: 'TagMap', where: { targetType: 1 } })

+ this.hasMany('items', { through: 'itemTagMaps' })

}

}

hasOne()

A hasOne() association also sets up a one-to-one connection with another model, but with a few sematic differences. At first glance it may look quite similar to belongsTo() or even hasMany().

The difference between hasOne() and belongsTo() is mainly at the position of the foreign key. hasOne(), like hasMany(), needs the foreign key to be added in the target model, while belongsTo() needs the it located in the initiating model.

The difference between hasOne() and hasMany() is subtle. When a model hasOne() of another model, the other model will be mounted as a singleton. When it hasMany() of another model, the mounted attribute will be a collection that contains all the target models instead.

In this example, a user has one shop:

class User extends Bone {

static initialize() {

this.hasOne('shop', { foreignKey: 'ownerId' })

}

}

The TypeScript equivalent with decorator is like below:

class User extends Bone {

@HasOne({ foreignKey: 'ownerId' })

shop: Shop;

}

And the shop belongs to the user:

class Shop extends Bone {

static initialize() {

this.belongsTo('owner', { className: 'User' })

}

}

The TypeScript equivalent with decorator is like below:

class Shop extends Bone {

@BelongsTo({ className: 'User' })

owner: User;

}

Choosing Between belongsTo() and hasOne()

As dicussed in the hasOne() section, the difference between belongsTo() and hasOne() is mostly at where to place the foreign key. The corresponding model of the table that contains the foreign key should be the one that declares the belongsTo() association.

For example, it makes perfect sense that a user should hasOne() shop, and the shop should belongsTo() an owner (which is a special type of user). Then the shops table should declare the foreign column called owner_id to make this.hasOne('shop', { foreignKey: 'ownerId' }) work.

There’s a bonus of reasoning this kind of differences between associations. If the business needs to allow a user to have multiple shops someday, we can just change the hasOne() to hasMany(), wrap existing code into a for (const shop of user.shops) loop, and then go get a coffee. There’s no need to touch code at the Shop model.